He launched the #vanlife frenzy - now he's swapped it for an off-grid cabin

Nov 5, 2020 • 8 min read

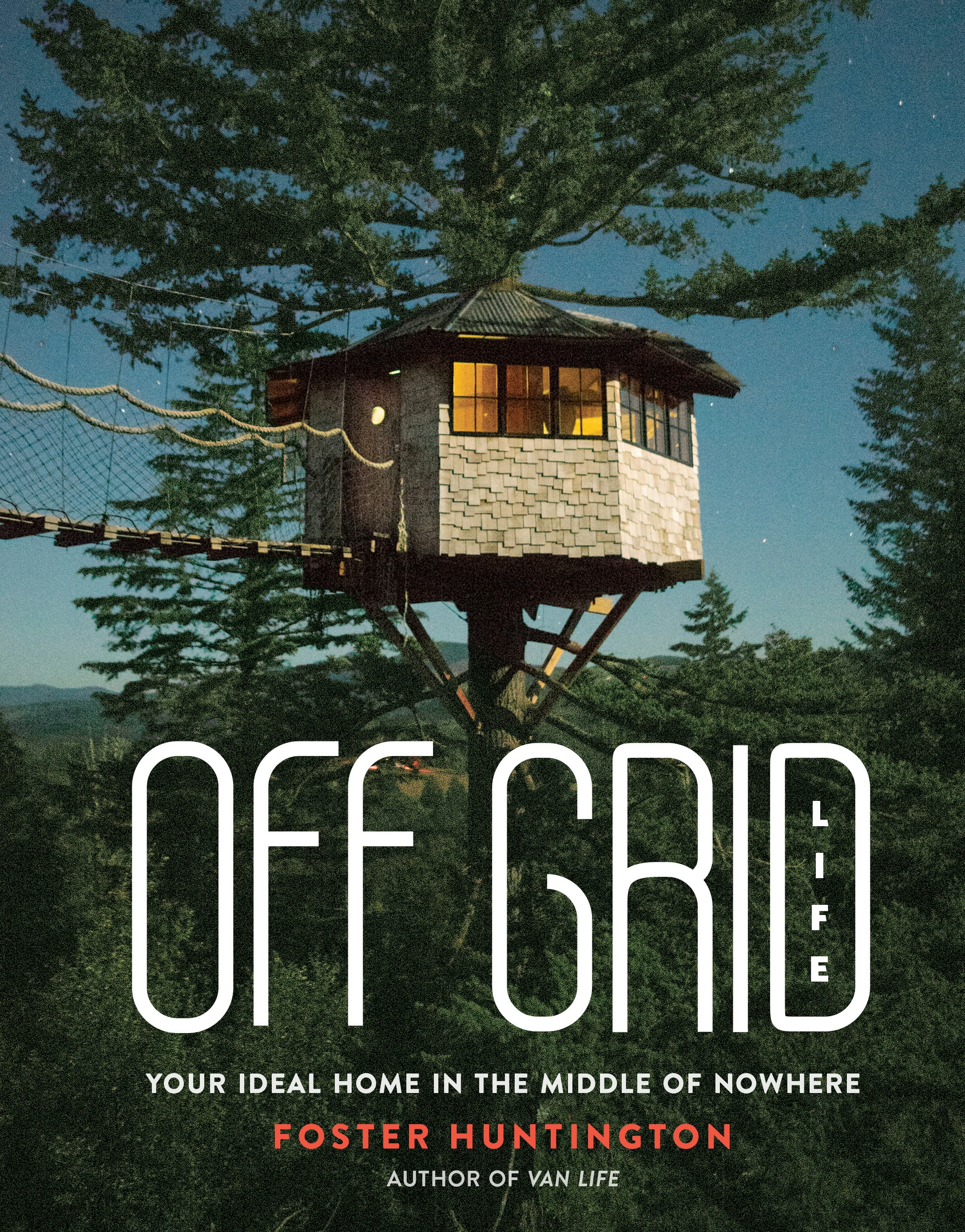

Foster Huntington and the treehouse he has built in Washington State.

Warning! This article will make you want to quit your job, delete social media and buy land in the mountains. Other side effects may include: building your own home or hitting the open road in an old campervan. Instagram’s #VanLife initiator Foster Huntington returns with a new book Off Grid Life: Your Ideal Home in the Middle of Nowhere – seducing us with a self-build lifestyle as the antidote to our frantic, digitalized lives.

By any show of restraint, it’s difficult not to be drawn into the life and photography of Foster Huntington. The bearded 32-year-old filmmaker/photographer/Instagram supernova from Skamania Country in Washington, near the Oregon border, takes the kind of ah-man-wish-I-was-there snaps that sew together isolation, inspiration, and human existence in a single shot.

Take the front cover of his latest coffee table book Off Grid Life: perched high up in a Douglas fir tree looking out across a canopy of evergreens and blanket of stars at dusk, the windows of a small hexagonal tree house glow a candlelight-orange telling us that someone is home. The photo is of Cinder Cone, the home Huntington built with several friends on five-acres of family-owned land in Columbia River Gorge – and it’s just one of nearly 100 alternative homes that feature in his latest title.

“I want people to re-evaluate and think about what an ideal dwelling looks like to them,” says Huntington, speaking about his fifth book via Zoom from the studio he’s also built at Cinder Cone. “We live in a time where convenience and comfort triumphs all, and I don't think that necessarily makes us any happier.”

When it comes to re-evaluating their world, Huntington has form. Back in 2011, he quit his job as a designer at Ralph Lauren in New York City and flew straight to Reno, Nevada to pick up an off-white VW Vanagon Syncro with a black nose that he would live in for the next three years. Overnighting in national parks and on friends’ driveways, he cruised around the backroads of the Western USA, Canada and Mexico, surfing, eating tacos and uploading photos to Instagram.

Then, all of a sudden, his #VanLife hashtag caught on and Huntington became something of a messiah in millennial travel, even if he didn’t mean to. His follower count went higher than his mileage and the hashtag traveled further than he ever did. It thundered around the world, being used more 8.5 million times to tag everything from sprinter vans parked by pristine lakes to surfboards flopped atop Type 2 VW Transporters, waves crashing in the background.

The upshot? Thousands of adventurous travelers packed up their lives, bought a van and aimed for that tarmac horizon. It became a small travel movement that Huntington captured in glorious, photographic beauty in his book Van Life: Your Home on the Road. “When I was doing it, it wasn't anywhere near as popular as it is now,” says Huntington. “Now there's a bunch of travelers on the 1 in California and the 101 in Oregon and Washington. Like a lot of international people – a lot of people from Europe who are on long road trips.”

There’s little doubt that at his social media height, with more than one million followers on Instagram, Huntington’s influence inspired others to follow his lead, but he also believes that people started to travel in vans because of the economic and cultural changes that followed the financial crisis of 2007–2008. This includes remote working. “I think traveling and living in a van is so much more accessible to people when you don't have to live somewhere to work,” he says. “It just makes more sense.”

Having stopped traveling full time in 2014, Huntington’s latest van is now parked at Columbia River Gorge, and he has spent the last few years meeting, interviewing and photographing self-build pioneers while he designed and built a tree house of his very own. In Off Grid Life, readers see inside the home of writer Lloyd Kahn, who has published more than 12 books on self-builds and off-grid living, as well as the artist Fritz Haeg, whose art commune Salmon Creek Farm was made entirely from salvaged materials.

But is it all that simple? Will the book have a generation reaching for the hammer and saw as they consider building a home of their own? Huntington says he’s always been good with his hands – his mum was a builder, his dad a real estate agent – but still building the tree house was a steep learning curve. “I learned a lot of carpentry when I was doing the tree houses. I learned a lot of carpentry skills as well tree climbing skills, because when you're building a tree house, you're kind of a tree climber first and a carpenter second. So I had the crash course in repelling and roping and tying knots.”

Others in the book share the same view: self-building is hard work. You will make mistakes. Nothing is perfect. But you’ll also have greater control of what you actually need and a greater satisfaction when you’re finished. Or, as Haeg puts it in the Off Grid Life: “I love that feeling of being amateur at something new.”

For Huntington, it was the build that he enjoyed the most. “Some of the happiest, most connected I've ever felt was when I was working on my tree house with all my friends,” he says. “Each day we were working on one kind of communal goal in terms of ‘alright, we need to get the windows in and we need to get the roof on’, and that's so much fun, and so rewarding.”

They scavenged for cheap building materials – redwood and cedar tiles from big-box stores, windows from failed luxury builds, rope bridge cord taken from old tugboats that motored along the Columbia River. At night they kipped in their cars, shared spliffs around the crackle of the campfire and drank cheap beer. Together they created something rather remarkable: two interconnected tree houses, a wood-fired sauna, and a smallholding for chickens and goats. Professionals then came in and added a skate bowl that looks out across the valley.

For legions of young people brought up in a screen-first world, there’s something particularly alluring about Huntington’s latest coffee table book. This physical photo collection of remote cabins, tents, earthships, boats, and tiny homes – interspersed by the thoughts and stories of those who built them – not only sell the reader the dream of living amongst the solitude of nature, but nudge them towards it too.

Horseboxes in front of big Californian skies, campervans by billowing campfires, wooden hideaways in deep thickets of evergreen trees, sailing yachts cutting froth around a coastline – all reminders that we all once lived among nature. We respected it. We cared for it. We proudly stood within it, unshackled by offices or Instagram or nine-to-fives.

Now nature is sold as a luxury. We pay for the pleasure of isolation. Digital detoxes and vacations in remote internet-free locations remind us that we’re connected to something bigger than the technology we’re currently using.

Huntington’s own tree house has the internet. He needs it for work – he’s off-grid, but online. “I think the reality is that for a lot of people, we need to be connected to the internet,” he says. “It allows people to live anywhere, you know? That's kind of like a trade-off. That, to me, is positive.”

But with firewood to chop, sheds to build, animals to tend, stop-motion videos to make and early morning walks to take with his cocker spaniel Gemma, the self-build lifestyle means Huntington has found less time to be on social media. Despite Tumblr and Instagram pushing him into the spotlight, he thinks this is a benefit to living off-grid.

“When I started the VanLife hashtag and when I started the tree house project, social media was a very different beast,” he says. “I think the algorithm – and serving content that way – is terrible for the fabric of society. It allows these businesses to just control everything we see based on what they think will get us to spend more time on the platforms and I think these technology companies are truly evil. So I don't have Instagram on my phone, I don't have Facebook on my phone, I don't have Twitter on my phone.”

So with Instagram so prevalent in modern life, does he think we need to rethink how we travel too?

“People go to Machu Picchu because they want to get the Instagram photo of them with the llamas and they want the selfie with Machu Picchu behind them,” he says. “People should travel for experiences, not for photo ops.”

Off Grid Life: Your Ideal Home in the Middle of Nowhere by Foster Huntington is available now.

You might also like:

Instagram's impact on travel

7 stunning eco-hotels for the environmentally conscious traveler in 2021

So your town got famous on Instagram. Here’s what will happen next…