My Kerry: a very personal guide to Ireland's most beautiful county

Jun 30, 2019 • 11 min read

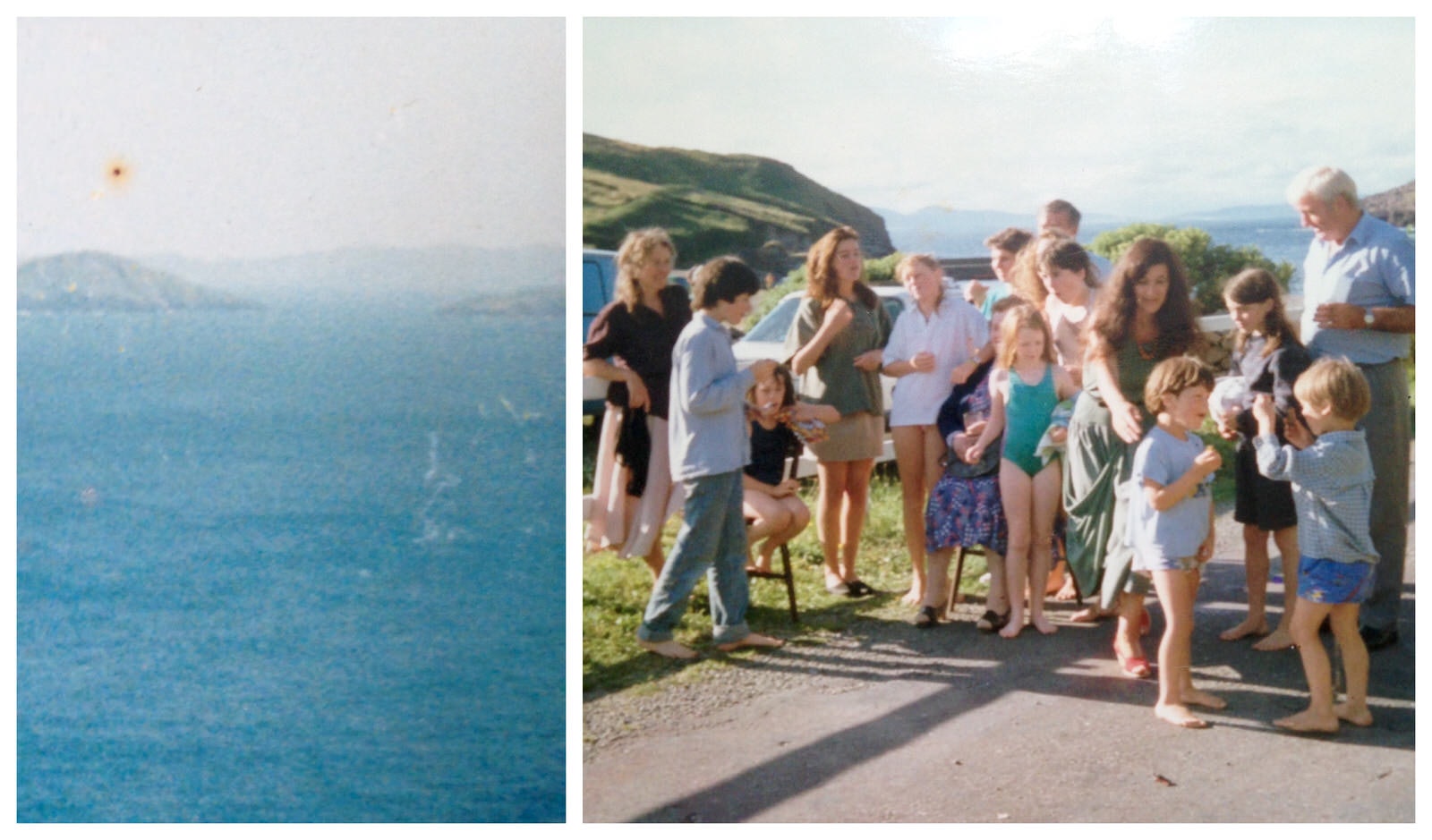

A view of Scariff Island (c) Oliver Huitson

The first place in Ireland to have a thriving tourist industry was Kerry. As far back as the 1800s, the lakes around Killarney were drawing visitors, including Queen Victoria, and today, it is still the most-visited place in the country. Tourists come, in their droves, to see the magnificent Ring of Kerry, Carrantuohill, Dingle, Listowel Castle, Inch strand, the gap of Dunloe, to visit Valentia Island, the Skelligs, the Blaskets. They come because it’s beautiful and wild, steeped in history, and they go away happy. Sometimes, they come again and who could blame them? But for writer Emily Hourican a visit at least once a year is a must. Because for her, Kerry is all those things, and more.

There is a place along the way between Sneem and Caherdaniel in Co Kerry, before you get to White Strand and Castlecove, where the road widens enough to stop the car and get out. By then, you are through the lush overgrown landscape around Parknasilla, and past the flatter, marshier expanses immediately outside Sneem. You have climbed high enough that the surrounds are rockier, more barren, and the view – sudden, always surprising – down to the vast Atlantic and out towards the islands of Deenish and Scariff lies before you.

Beyond, further out again, the Skelligs are a presence but not yet visible.

Every year that I return to this corner of Kerry, this is where I like to stop, stand, and look. There are days you can see no further than the ground at your feet, because the mist has rolled down and smothered everything. And there are days when you can see right out to what the monks who made their lives on Skellig Michael believed was the edge of the universe, the end of the road; the last stop before God.

That’s why they were there, perched on a rocky outcrop far out into the wild Atlantic, eking an existence and worshipping their God. They were there because they believed that further from land and humanity meant closer to that God. And anyone who has ever stood among those beehive huts on Skellig Michael and looked around them, will believe they were right. From that vantage point, even though our knowledge of geography might tell us that America lies beyond, it is impossible to believe it. The air and the wind, the smell of heather and wheeling sea birds coming in to land on Skellig Beag, tell anyone who is paying attention, that this is Somewhere Else; somewhere that the prosaic laws of geography do not apply. Somewhere that stands on the edge, in the breach, between one world and the next. A veil you can almost lift, or peer through, just by being there.

Back on the road, poised above Caherdaniel, Skelligs still out of sight, as I stand and breath, taking in the smells of Kerry that are every bit as distinct as the sights, I know, every year, that I am about to enter the orbit of that other world. That I am home.

This is my Kerry – a corner of the Iveragh peninsula that stretches from Cahirciveen to Sneem. This is my place. The source to which I return. Every point along the road holds a memory, or so it feels.

I wasn’t born or brought up here. I was born in Belfast, in 1972, amidst bombs and atrocities. Brought up, mostly, in Brussels, a city that felt sophisticated and free when I compared it with the few scattered years we spent in Dublin, a city I then found shabby and glum, before I came to love it as an adult. Every summer, we came back from Belgium to Ireland for five or six weeks. I remember summers spent in Clare, in Mayo, when I was very young and then, from the age of maybe 10, it was Kerry that we always came to.

I didn't come, then, because I wanted to. I came because that was where we went, all eight of us; my parents, my five siblings. Later, as a teenager, I came very much despite not wanting to spend three or four weeks in the middle of nowhere. By then, we had settled on a house outside Cahirciveen, perched over a tiny cove, Cuas Crom, still the most perfect swimming spot I know, enclosed by cliff arms that keep the water relatively calm, with a pier at the mouth of the open sea that is an ideal distance from shore for a demanding but not daunting swim.

Not that I swam much as a teenager. Neither did I do much of anything. I remember a lot of toasted brown soda bread with butter, and sausages; books and crosswords because we had no TV, board games with pieces missing: (‘remember, the bottle top is a knight, the plastic brick is a pawn…’). I was a pretty indolent teen, unwilling to swim unless the sun shone (which it didn’t, much), indifferent to the landscape around me, unwilling to walk much further than the Ring Fort up the road, or take more than a gentle bike ride along the narrower paths to pick blackberries. I was the one always quick to say ‘I’ll stay home and cook’ when my parents suggested a hike up Bolus head or a trip out to the Skelligs. That, I knew, would give me hours in which to lounge, smoke, and fret about what I was missing back home, while still giving enough to time to prepare new potatoes and wild salmon which, in my memory anyway, is all we seemed to eat when in Kerry.

There was the odd day trip, to a regatta or other ‘event’; a variety of visits, from cousins and friends, but mostly, the point of these holidays, for my parents, was to be as far away from civilisation as possible. The house had no phone as well as no TV, and was hard to find, tucked down a road that wasn’t signposted, and so directions relied on landmarks: a fork in the road, the barracks, a haunted house (that house, on the Cahirciveen-to-White-Strand road, really is the most haunted place I know; a blackened, burnt-out shell of a once-elegant manor that has blight and malevolence in every falling-down line so that I won’t even eat blackberries picked from the abundant bushes around it).

These directions were so fallible and weather-dependent (on a bad day, you hadn't a hope of spotting the tumble-down ring fort from the road, the point at which you were supposed to turn), so my brothers and sisters and I would be sent into town, to loiter at the end of the bridge over the estuary outside Cahirciveen, often for hours, waiting for a car to stop and people, sometimes strangers, to say ‘are you Houricans?’, whereupon we would get in and guide them to the house.

For years the house was called, locally, the Birmingham House, after the man who built it, even though he hadn’t owned it in forever. That is the house my father died in, from a heart attack that killed him long before the ambulance – rung for from the house up the road, by neighbours woken out of sleep after midnight – could arrive. And further into town, just before the bridge, is the ‘old graveyard’ where he is buried.

In the years that followed, I went to Kerry every year for his anniversary, August 14. And then I stopped going. I stopped wanting to go. I was in my 20s then, drawn by the heat and excitement of Spain, Italy, France, Greece. Why would anyone go to Kerry, I wondered, when there was all the world to discover? There still is all the world to discover, or most of it, but I have found that I prefer the familiar to the strange.

It was when I started having children of my own that I began to go back to Kerry. I have loved showing them the places I went to as a child, love even more when they now recognise such places for themselves. ‘Can we get icecream from the Valentia Island Dairy?’ or ‘are we doing Bolus Head this year?’

My latest book, my fourth novel, 'The Outsider', is largely set in Kerry. Of all my books, this is the one I have enjoyed writing the most, because that is the landscape I like to walk in my mind. Describing the places I love best, using them as settings, almost as characters, in this book, was a joy. As a result, the landscape and, even more so, the sea around Kerry are just as instrumental to the action as the characters.

I have written a Kerry that is very personal. This isn’t an ordinance survey map. I’m not sure you could navigate from what I have called The O’Reilly’s house down to Derrynane beach exactly as I have described it, but every emotional breath taken along the way is true, to me.

Three years ago I had cancer, of a type that involved a lot of radiation to the head and neck. This, in turn, meant a mask, moulded precisely to my head, tight, constricting, into which I was strapped every day for 35 days, before being bolted to a steel table, behind a heavy radiation-proof door, for 20 agonising minutes. The discomfort was considerable, the claustrophobia that shimmered at the peripheries so real, that the only thing to do was abstract myself. Walk elsewhere in my mind. Find a place that could keep me from spiralling into terror and hysteria. Ballinskelligs beach is the place I chose. I walked it every day in my imagination for those 35 days, looking at stones and shells, listening for the in-and-out of the waves, watching the way the light fell then receded and the sound of wind through dune grass.

Ultimately, I think we all get to choose where ‘home’ is. It isn't just, as Robert Frost put it, the place where, “when you have to go there, they have to take you in.” It’s the place where, when you need to be taken in, you have to go there.

The Outsider by Emily Hourican is out now, published by Hachette Ireland

My Kerry

There is, I think, no limit to the wonderful things to do and see in Kerry. But these are the places I like to visit every year, a kind of score-card of my personal must-dos. I couldn’t leave without feeling I had ticked them all off for another year.

Bolus Head

Drive as far as the Cill Rialaig artists’ retreat, park and walk up as far as the road will take you. On your left as you ascend, dramatic cliffs plunge down towards the Atlantic. You will pass ancient, ruined famine cottages, standing stones, sheep, the odd car, but very few walkers.

The stone forts of Cahergal and Leacanabuaile

Both have been substantially rebuilt in recent years, so that they are now a tiny bit too new and perfect, but still fascinating. Cathergal has dry stone walls around six metres high and some three metres thick, one of the best examples of an early medieval stone forts to be found on the ring of Kerry, while excavation within Leacanabuaile produced Iron and Bronze Age objects.

The Skelligs

Ok, the last time I was there, a man leapt from behind a beehive hut shouting ‘where’s Skywalker?’, but really, nothing and no one can ruin this. Boats still leave from Portmagee most days during the season, but be ready to book months in advance as they tend to fill up fast.

Ballinskelligs Beach

A tiny bit off the beaten track, certainly in comparison with Derrynane, this has fine white sand, spectacular views and clear cold water. A new car park has made it more accessible – which is both a good and bad thing.

Caherdaniel

For all that it’s busy, Derrynane is still among the most beautiful beaches in the world. Walk through the dunes – watch for prettily-coloured sea snails under foot – and have tea and excellent cake at Derrynane House.

Cuas Crom Beach, Cahirciveen

My favourite place to swim – a safe, enclosed cove with enough sand for kids to play, and enough water, regardless of tide, to always swim. The day after a high wind or storm, this is a great place to beach-comb.

O’Neills The Point, Renard Point, Cahirciveen

You need to get here by 5pm if you have any hope of a table, but if you’re smart and time it right, this is the finest and freshest seafood around. Monkfish, wild salmon, crab, prawns, lobster on a good day. Look no further.

Valentia Island

Head down to the rocks to check out the tetrapods, some 350-370 million years old, then walk to the highest point of this beautiful island. Take a swim at the tiny subtropical Glanleam beach and finish up with an ice-cream from the Valentia Island farmhouse Dairy, where milk for the ice-cream comes from the cows in the field beside you.

Get more travel inspiration, tips and exclusive offers sent straight to your inbox with our weekly newsletter.

https://shop.lonelyplanet.com/products/best-of-ireland-travel-guide-2

Take your Ireland trip with Lonely Planet Journeys

Time to book that trip to Ireland

Lonely Planet Journeys takes you there with fully customizable trips to top destinations – all crafted by our local experts.