Why Belize is better for scuba diving than the Great Barrier Reef

May 21, 2024 • 5 min read

Belize’s popular Great Blue Hole isn’t the country’s only worthy dive site. © iStock

It’s one thing to know lobsters can be blue. It’s another thing to see one up close with its sapphire shell, claws, legs and antennae sprawling in every direction. I watched it scurry across the sandy floor 18m (60ft) beneath sea level and reminded myself to breathe in, breathe out calmly, just as my divemaster taught me. This was not the sad brown crustacean I’d seen trapped in dirty tanks at a certain chain restaurant; this was ocean life at its purest. This was Belize.

Diving in: beyond the Great Blue Hole

Most experienced divers go to Belize on a mission to explore its Great Blue Hole, a massive sinkhole in the Caribbean Sea stretching 300m (984ft) across and 125m (410ft) deep. You can see it from space, and inside it’s filled with caves and stalactites to thrill the bravest underwater adventurers. Meanwhile, I started my training in a pool in midtown Manhattan, where the scariest thing floating by was a used bandage.

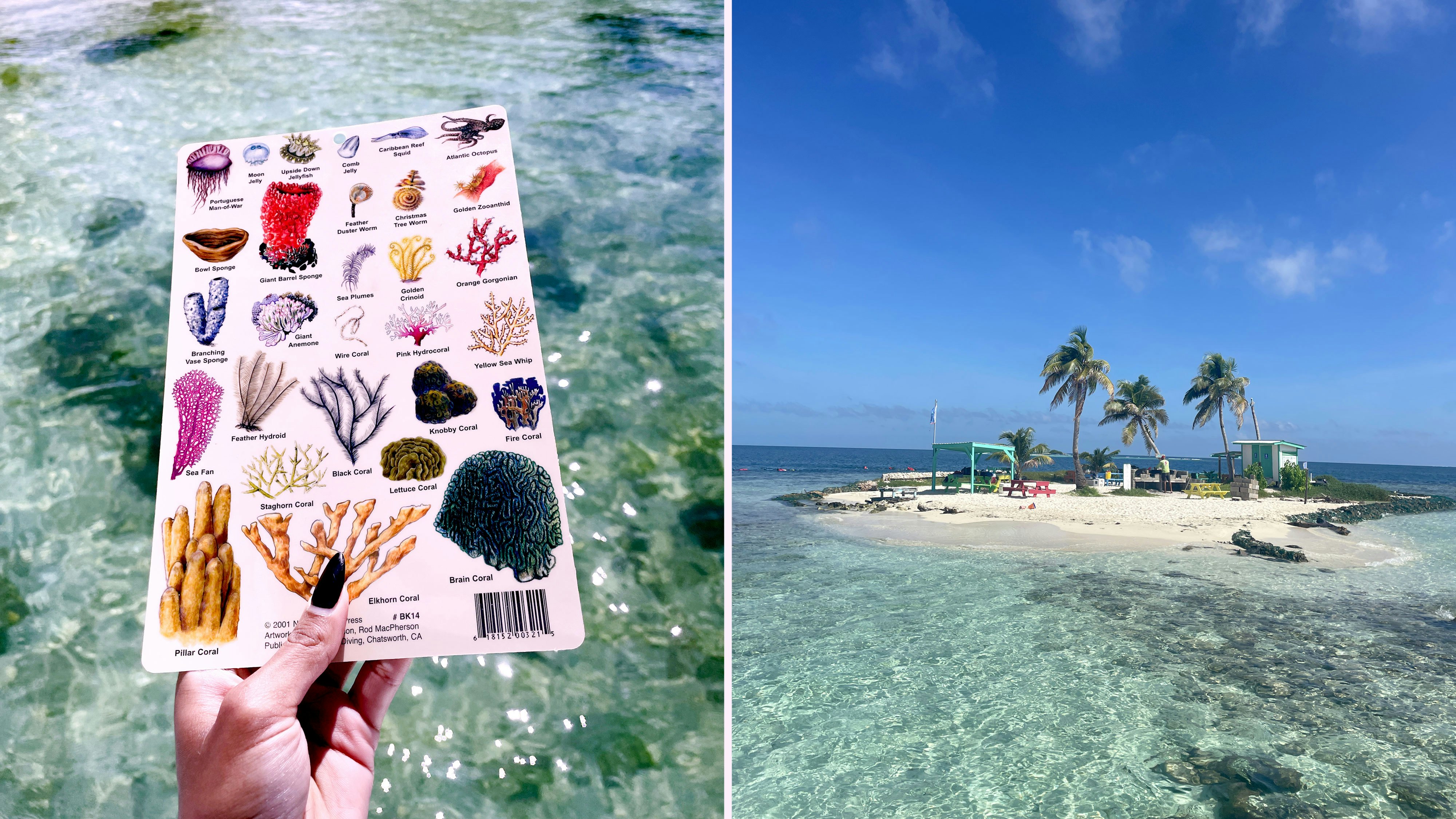

So I might not be the Great Blue Hole’s target audience, but I still wanted to squeeze in a dive somewhere to use the open-water certification I got in 2019, right before a global pandemic crushed my dive trip dreams. Travel Belize took me to Silk Caye, an island and reserve off the coast of Placencia, where snorkelers can also enjoy its shallower waters while divers get their scuba on.

I dove in with low expectations and was promptly greeted by a (harmless!) nurse shark. In just one dive, I saw several more of these sharks, plus lionfish, groupers galore, angelfish, barracuda and, yes, the afforementioned lobster. The highlight, however, were the loggerhead sea turtles that swam next us while snorkeling; one got so close, its fin brushed my arm! I was amazed. I never thought I’d have the privilege of getting this intimate with marine life.

The Great Barrier Reef: not so great?

I went to Belize for a range of active experiences on land – ziplining through treetops, horseback riding to Xunantunich archaeological site and biking through Hopkins village – but I wanted to squeeze in a dive. As a newbie, I haven’t had the opportunity to dive in many destinations, especially diver favorites like Thailand, the Galápagos, the Maldives, Indonesia, the list goes on. But a year before I made it to Belize, I crossed the number-one spot off my bucket list: the world-famous Great Barrier Reef. I started in Sydney and backpacked up Australia’s East Coast, ending in Cairns for a week. I lived on a boat for several days diving up to four times daily alongside guides for peace of mind.

With their expertise, I quickly got back into the swing of things – BCD on, check the oxygen level, adjust buoyancy, calculate a safety stop – after being out of practice. Still, I struggled. I attempted one night dive, but my gear wasn’t fitted properly and, in combination with the pitch-black darkness, I panicked and swam back to deck before descending. My meds barely countered the sea sickness, and the waves were so choppy, I had a hard time seeing anything on a snorkeling safari led by an onboard marine biologist.

Back on dry land, my takeaway from this experience was pride at myself for stepping outside my comfort zone, but also disappointment at how little I’d actually seen on my successful diving days. Maybe it was the locations we’d docked, my lack of diving experience, the water conditions and/or the hype around this iconic reef, but I felt underwhelmed. Having been awestruck by the stunning coral when I was snorkeling off the coast of Cartagena, Colombia – the trip that convinced me to get my diving certification – the monotony of the scenery on the iconic Barrier Reef really hit home how human-caused climate change has impacted these precious ecosystems and how important conservation is to protect them in future.

Protecting coral reefs

The Belize Barrier Reef Reserve System, which includes the Great Blue Hole, was designated as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1996 and is the world's second-largest reef system after the Great Barrier Reef. Locals on the ground claim it’s the largest living barrier reef globally, which is difficult to confirm, but I certainly saw a lot more underwater life there in one day than I did in a week off the coast of Queensland.

Climate change has wreaked havoc on coral, and I wish I’d made time to see some of the preservation projects happening in Australia when I visited, because I got to see that work happening in real-time in Belize and wow, is it cool.

In Placencia, the nonprofit Fragments of Hope is building coral nurseries near the peninsula to restore damaged areas. In simplest terms, this involves taking living pieces of coral and cementing them to dying coral so the living part can revive the dying part. I snorkeled around the nursery near Laughing Bird Caye and could see the saturation and vibrance coming back to the ocean floor.

Meanwhile, the Great Barrier Reef Foundation is conducting its own restoration initiatives – including something called coral IVF and freezing coral tissue in liquid nitrogen – and as my diving journey continues, I’m eager to learn more about how I can contribute to conservation efforts on an individual level.

In the meantime, I’ll continue slathering on my reef-safe sunscreen to protect myself and all the beauty I’m lucky enough to witness under the sea – in Belize, Australia and beyond.

Deepa traveled to Belize on a trip hosted by Travel Belize. Snorkeling and diving in Placencia was provided by Splash Dive Center. Lonely Planet does not accept freebies in exchange for positive coverage.